Confirmation

M00: Pediatrics - General

Updated:

Reviewed:

Introduction

This comprehensive guideline is designed to equip BCEHS employees with the knowledge necessary to recognize and address the unique needs of pediatric patients. It acknowledges the critical importance of tailoring medical management to the specific physiological parameters of different age groups and provides in-depth information on the distinct anatomical structures, physiological functions, and developmental factors that paramedics must consider when assessing and treating pediatric patients within the prehospital realm.

By gaining understanding of both the commonalities and variations between adult and pediatric patients, paramedics will be better prepared to deliver care that is safe, effective, and compassionate to patients across the entire age spectrum. This readiness extends to routine medical situations as well as critical emergencies, ensuring that optimal outcomes are achieved.

Essentials

For clinical consideration within BCEHS, pediatric patients are those who are ≤ 12 years of age, whereas adults are defined as > 12 years of age or showing signs of puberty. There is widespread variation on this definition across BC health authorities. This does not apply to matters of consent.

Children differ anatomically and physiologically in comparison to adults in a number of ways. The table below highlights so of the key distinctions:

| Anatomical and Physiological Differences | Implications for the Pediatric Patient |

| Children have a larger head and trunk compared to the rest of their body | More susceptible to heat and fluid loss |

| Children have small and narrow airways, larger tongues, shorter tracheas, more elastic cartilage, and are obligate nose breathers for the first 2-4 months of life | Increased risk of airway obstruction and ineffective oxygenation in the event of respiratory illness |

| Children have an increased metabolic rate and increased fluid requirements, as a greater percentage of their body weight is water | Require more energy and consumer more oxygen to sustain their basal metabolic rate, and in cases of decreased oxygenation or decreased intravascular volume, they can dehydrate and deteriorate quickly |

| Children have an underdeveloped nervous system response such as shivering, vasoconstriction, and the ability to sweat. Infants under 6 months cannot shiver, and rely on brown fat metabolism to generate heat. | Unstable temperature control requires close monitoring to ensure that normothermia can be maintained. Children can get cold quickly when exposed for examinations or procedures. |

General Information

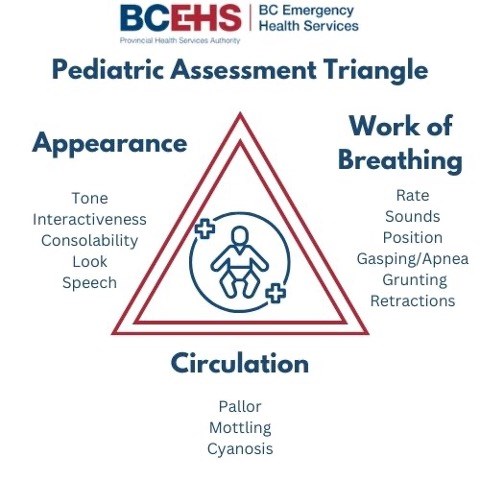

General Appearance: “Tickles” TICLS

When assessing the patient’s general appearance, remember the mnemonic TICLS, which stands for Tone, Interactiveness, Consolability, Look and Speech.

- Tone: Muscle tone. Is the patient demonstrating independent, voluntary movement of all four extremities? Or are they laying limp/flaccid? When an extremity is touched, how do they respond? Are they quick to pull away or tense the arm/leg? Or do they let it drop heavily back to the original position?

- Overarching question: Is the child moving appropriately, or are they floppy or listless?

- Interactive: This component will vary greatly depending on age of the child. Pediatric patients 1 to 5 months interact by opening their eyes, moving their arms and legs, or crying when they are unhappy. By 6 months of age, they can smile, and grab onto things you present in front of them. By 8 months, children are usually learning how to crawl, and can sit up independently.

- Overarching question: How alert is the child?

- Consolability: Can the parent calm the patient as they usually do, or are they unable to help them regulate? Children ages 3-5 may have difficulty communicating when they are in pain or discomfort, and their caregivers may be the best source of information about their normal behaviour versus their current response. Does the child respond the same to your presence as a stranger as they do to the comfort of their caregiver?

- Overarching Question: Does the child settle like they usually would?

- Look/Gaze: Do they make eye contact? Are their eyes tracking or vacant stares? Do their eyes stay closed? Does the child look to the caregiver? Did they notice you enter the room?

- Overarching Question: How does the child visually observe the environment?

- Speech/Cry: Are they attempting to speak? Sick children may be unable to express themselves. Crying again can be a good sign! It safeguards the practitioner that the patient has an open airway and is effectively breathing. Note any abnormal sounds to the cry. Is there a high pitcher wheeze present? Is there a barking-like cough?

- Overarching Question: Does the child speak/cry as usual, or is something unusual?

Final general impression question: Is there anything concerning in the appearance of the child?

Work of Breathing

Children’s breathing should be noiseless, effortless, and painless.

Observing changes in respirations should be made before further assessment to avoid causing the child to become upset and changing their respiratory efforts from baseline. Changes in pediatric respirations are much more subtle than in adults and may require close attention to distinguish. This will require removing the shirt or lifting it to assess adequately. Note the rate, rhythm, and depth of respirations. Notice any patterns. Children up to 5 are belly breathers - meaning they utilize their stomach muscles with inhalation. This will cause their abdomen to protrude with inhalation and retract with exhalation.

※ Pearl: From a distance, you can ask the caregiver to assist you in your assessment by lifting or removing the child's clothing, if appropriate. The “doorway” respiratory assessment performed as part of the PAT can yield valuable information, informing the practitioner on possible aetiologies associated with specific abnormal breathing patterns and sounds.

Respiratory patterns

Quick, shallow breaths accompanied by extended exhalation are commonly observed in cases of air trapping, such as those seen in conditions like asthma, bronchiolitis, or when a foreign object obstructs the airway beyond the carina. This breathing pattern can also occur due to chest or abdominal discomfort or dysfunction in the chest wall.

Other concerning breathing patterns include:

- Kussmaul respirations (rapid and deep breathing pattern potentially indicating metabolic acidosis)

- Cheyne-Stokes or ataxic respirations (variable rates of breathing associated with periods of apnea can be indicative of CNS damage or injury)

- Paradoxical breathing (chest collapses on inspiration and abdomen is pushed outward, can be a sign of fatigue or muscle weakness)

Please review this video for further information on these breathing patterns.

Accessory muscle use

- Nasal flaring: exaggerated opening of the nostrils during inspiration, is a subtle form of severe accessory muscle use

- Head bobbing: extension of the head and neck during inhalation and falling forward of the head during exhalation, is most likely to be seen in infants and can be easily overlooked

- Chest wall muscle retractions and abnormal movement: muscles surrounding the ribs, sternum and clavicle retract inward due to high intrathoracic negative pressure generated by increased respiratory effort Look at the child's chest. Notice any indrawing between the rib spaces, around the trachea (tracheal tugging) or directly underneath the diaphragm.

- Abdominal breathing: Characterized by thoracoabdominal dissociation, in which the chest collapses, and the abdomen protrudes on inspiration, may be normal in infants, but, beyond infancy or in patients with poor muscle tone, is concerning for respiratory muscle fatigue.

Please review this video for more information and examples

Final breathing question: Are you concerned about their breathing?

Circulation

Evaluating the adequacy of systemic blood flow is a critical element of pediatric patient care. Pediatric patients communicate valuable information about their circulatory health through the condition of their skin. In healthy children, the skin presents with a natural color and feels dry and comfortably warm. Any deviation from this normal state should immediately catch the attention of healthcare providers. It is crucial to consider the child's ethnic background and the lighting conditions in the environment when assessing the child's skin.

During the PAT, pay close attention to a patient’s circulation to the skin. When approaching the child, note the general appearance of their skin.

- Are they pale/white in appearance?

- Are they red/flushed?

- Do they appear to have a grey/blueish tone (cyanosis) to their skin?

Consider asking the parent or primary caregiver: Does the child look their usual colour?

Pallor: Paler than normal. Pallor can be a sign of anemia, hypothermia or hypoperfusion.

MOTTLING = RED FLAG FOR HYPOPERFUSION

Cyanosis: Blueish discoloration of skin. Predominant around lips. Cyanosis may indicate hypoxia, a lack of oxygen.

CYANOISIS = RED FLAG FOR HYPOXIA

Lightly press down on the nailbed using a finger or toe (which may be preferred in children). How long does it take to return to baseline colour? 1 second? 2 seconds? Anything over 2 seconds can be a sign of decreased perfusion.

Lightly pulling a section of skin on the hand or chest, does it snap back into place quickly? Or does it “tent” and return slowly? This can be a great sign of hydration/dehydration.

Are there any rashes present? If so, where are they located, and how would you describe them?

Final breathing question: Are you concerned about their circulatory state?

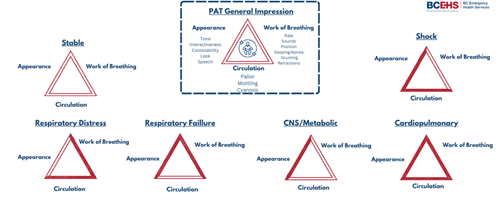

Pediatric Early Warning System

Efficiently conveying and documenting potential signs of illness in a child, as indicated by the Pediatric Assessment Tool (PAT), is of utmost importance.

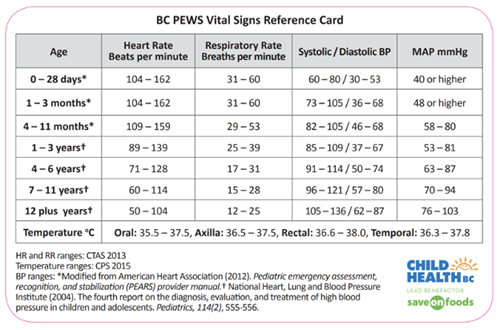

Internationally, Pediatric Early Warning Systems (PEWS) play a vital role in proactively recognizing and addressing deteriorating health conditions in pediatric patients who are admitted to hospitals. “The PEWS provides evidence-informed methods to assess children in different age groups, using vital signs parameters and risk indicators supported by evidence to be reliable indicators of deterioration” (Child Health BC, 2023). Leaders and healthcare practitioners within the British Columbia (BC) health authorities have recognized the critical need for the widespread adoption of PEWS in healthcare facilities catering to children across various service tiers. This includes extending its implementation to BCEHS. Using the PEWS early warning score, along with the PEWS vital signs reference card will align BCEHS practices with the rest of the healthcare team and minimize margins for error.

BCEHS paramedics should have awareness of the factors associated with the risk of pediatric clinical deterioration. For PEWS this consists of 5 risk factors: Patient/Family/Caregiver Concern, Watcher Patient, Communication Breakdown, Unusual Therapy, and PEWS Score 2 or higher. (Childhealth BC, 2023).

Calculating Weight

Weight based dosing

It is recommended to use the following methods in order of most accurate to least accurate:

- Parent or primary caregiver estimation is most accurate (within 10 percent of actual body weight approximately 80 percent of the time

- Use of length-based measurements (eg, Broselow, Handtevy, PAWPER, or Mercy tapes)” (Fuchs, 2023) . For example, the Broselow tape provided a weight estimate within 10 percent of actual weight 54 percent of the time

- Age-based methods can be used but will often be highly inaccurate. We recommend using the following formula for patients aged 1 to 10 years: Weight (kg) = 2x(age in years)+8