Confirmation

M02: Pediatrics - Circulatory Emergencies

Updated:

Reviewed:

Introduction

Shock is a dynamic and unstable pathophysiologic state characterized by inadequate tissue perfusion [1]. Shock develops as the result of conditions that cause decreased intravascular volume, abnormal distribution of intravascular volume, and/or impaired cardiovascular function. These conditions can then cause:

- Insufficient circulating blood volume (preload)

- Changes in vascular resistance (afterload)

- Heart failure (contractility)

- Obstruction to blood flow

The leading cause of pediatric shock globally is hypovolemia resulting from gastroenteritis [2]. The widespread adoption of oral rehydration therapy has significantly decreased mortality rates in these cases. Another significant contributor to pediatric mortality is trauma, including instances of hemorrhagic shock. Severe sepsis is also a common occurrence among children worldwide. It particularly affects low birth weight newborns, infants under one month old, immunosuppressed individuals, and children with chronic debilitating conditions. Cardiogenic and obstructive shock are relatively rare occurrences in the pediatric population.

The initial signs of shock may be subtle in children and infants as their compensatory mechanisms are very effective. A child may lose 25% of their circulating blood volume before becoming hypotensive [3]. When the compensatory mechanisms fail, the child progresses quickly to decompensated shock where the “classic” signs and symptoms of shock are present such as: tachycardia, pallor, cold extremities, and altered levels of consciousness. When this occurs, cardiopulmonary arrest may be imminent. Key considerations when assessing pediatric patients in potential shock states:

- Compensatory Mechanisms: Children are often better at compensating for certain medical conditions compared to adults. Their bodies may maintain stable vital signs for a longer period before decompensating, which means they can hide signs of illness or shock until they reach a critical stage.

- Early Recognition and Intervention: Recognizing signs of shock in pediatric patients early on is crucial because they can deteriorate rapidly once their compensatory mechanisms begin to fail. Timely intervention is essential to improve outcomes.

- Observation at Rest: One way to identify shock symptoms in children is by observing them while at rest. This means paying close attention to their overall appearance and behavior, as well as monitoring vital signs like heart rate and blood pressure.

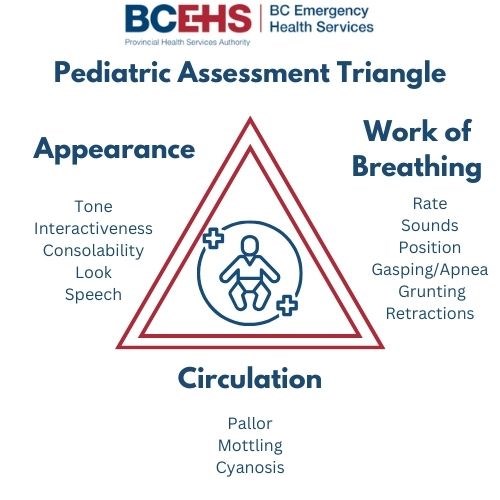

- Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT): The pediatric assessment triangle is a tool used to quickly assess the overall condition of a pediatric patient. It consists of three components:

- Appearance: This refers to the child's overall appearance, including their level of alertness, interaction with the environment, and skin color.

- Work of Breathing: It involves assessing the child's breathing effort, such as retractions (visible sinking of the chest or ribs during breathing), grunting, or abnormal breath sounds.

- Circulation: This component looks at the child's heart rate and perfusion, including skin temperature, capillary refill time, and pulses.

- Transport to the Emergency Department (ED): Any pediatric patient showing signs of shock or concerning symptoms should be promptly transported to the nearest appropriate medical facility, typically an Emergency Department. Early access to specialized care is crucial.

- Basic Priorities: At a basic level, there are several priorities when managing pediatric patients in shock, including:

- Adequate Oxygenation: Ensuring that the child is receiving enough oxygen to meet their body's needs.

- Appropriate Patient Positioning: Positioning the child in a way that maximizes their comfort and respiratory function.

- Fluid Administration: Administering fluids as needed to help restore circulating blood volume and improve circulation.

Essentials

- Know and be familiar with normal vital signs for given ages. Use BC PEWS vital signs reference card for most accurate parameters.

- Classic systems-based shock categories are septic, hypovolemic, anaphylactic, cardiogenic, obstructive, and neurogenic.

- Compensated shock: An adequate age-appropriate blood pressure is maintained

- Decompensated shock: Classic signs of shock present: Tachycardia, altered level of consciousness, pale skin, cool extremities

- → Shock states

- → Pediatric sepsis criteria

Additional Treatment Information

- Treatments must be targeted to the underlying cause. Vascular access is critical, but not all problems are responsive to fluid.

Signs of shock or other serious illness may mimic those in adults, but may also include:

- Tachycardia/bradycardia

- Pale/cool/mottled skin

- Capillary refill > 2 seconds

- Narrowing pulse pressure

- Tachypnea

- Relative flaccidity

- Change in level of consciousness (LOC) – especially failure to recognize/respond to carer(s)

In addition to oxygen, vascular access, and patient positioning, type-specific priorities are:

- Septic shock: 10-20 mL/kg crystalloid bolus, early antibiotics, vasopressors, steroids, and blood products

- Anaphylactic shock: EPINEPHrine 0.01 mg/kg, 10 mL/kg crystalloid bolus (repeated as necessary), vasopressors, and steroids

- Hypovolemic: 20 mL/kg crystalloid bolus, packed red blood cells, platelets, and plasma

- Cardiogenic: 5-10 mL/kg crystalloid bolus (Clinicall/TA consult), arterial line monitoring, vasopressors, inotropes, and chronotropes

- Obstructive: Identify and treat cause

- Neurogenic: 10 mL/kg fluid bolus (may repeat as necessary), vasopressors, and inotropes

General Information

Interventions

First Responder (FR) Interventions

- Place the patient in a position of comfort, as permitted by clinical condition; in general, this will include laying the patient supine and keeping them warm.

- Provide supplemental oxygen as required

- Conduct ongoing assessment and gather collateral information, such as medication and identification documents

- Communicate patient deterioration to follow-on responders

- Manage airway and breathing as required

- → B01: Airway Management

- Most pediatric airways can be effectively managed with proper positioning and an OPA/NPA (as per license level) and BVM without any requirements for further airway interventions. The gold standard for airway management is a self-maintained airway. Two-person bag-valve mask, with a viral filter attached and a tight seal, is the preferred technique for airway management in pediatric resuscitation and is reasonable compared with advanced airway interventions (endotracheal intubation or supraglottic airway) in the management of pediatrics during a cardiac arrest in the out-of-hospital setting.

Emergency Medical Responder (EMR) & All License Levels Interventions

- Expedite conveyance

- Assess for treatable cause of shock

- Consider intercept with additional resources

Primary Care Paramedic (PCP) Interventions

- Consider vascular access while en route; depending on suspected pathology, consider volume replacement (in patients ≥ 12 years of age)

- Consider reversible causes:

Advanced Care Paramedic (ACP) Interventions

- Attach monitor and evaluate rhythm for cardiac disturbances or arrhythmias secondary to shock physiology

- Consider vascular access

- Consider treatable causes

- Consider vasopressors

Critical Care Paramedic (CCP) Interventions

- Aggressive fluid replacement including blood products for suspected hemorrhagic shock

- Maintain normothermia. Actively rewarm if necessary

- Ultrasonography to assess pneumothorax, tamponade, and cardiac contractility

- Post-return of spontaneous circulation care:

- Advanced airway

- Crystalloid bolus 20 ml/kg IV/IO

- EPINEPHrine infusion

Evidence Based Practice

Supportive

Neutral

Against

Supportive

Neutral

Against