Confirmation

M06: Pediatrics - Cardiac Arrest

Updated:

Reviewed:

Introduction

In 2021 and 2022, 80 out of a total of 10,596 BCEHS calls pertaining to children aged 0 to 12 years were coded as cases involving respiratory or cardiac arrest. This represents 0.8% of overall pediatric calls. While infrequent, these occurrences, categorized as "High Acuity, Low Occurrence" (HALO) calls, can be inherently stressful. It has been documented that Survival is less than 10% for pediatric patients following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (Tijssen,2015).

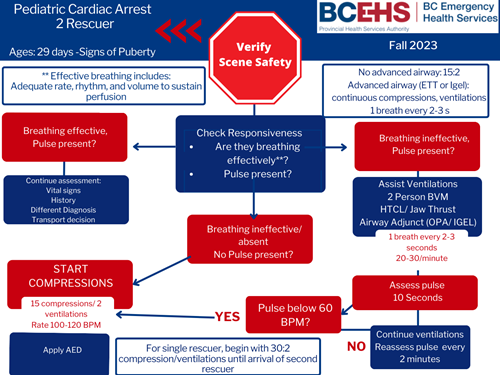

When managing pediatric cardiac arrests, priority is placed on delivering high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in conjunction with effective airway management. It may be challenging to immediately discern if a child's pulse is below 60 BPM. One partner may begin establishing airway management techniques if intrinsic respirations are deemed ineffective, while the other partner can focus on physically obtaining an accurate pulse reading. This may seem to prioritize airway management over initiation of compressions but in reality, these interventions should be happening simultaneously.

Upon establishing optimal oxygenation and proficient CPR, the attachment of a defibrillator assumes significance to discern the presence of a shockable rhythm. Pediatric cardiac arrests are not frequently cardiac in nature, so the application of a defibrillator should be considered only after establishment of effective airway management and high-quality CPR. Special considerations for cases involving blunt chest trauma, electrocution, cardiac history, or congenital heart anomalies may warrant expedited defibrillator application, given the heightened probability of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation.

Pediatric cardiac arrests display distinct characteristics in comparison to neonatal and adult arrest cases. Unlike adult cardiac arrests which are typically abrupt, pediatric cases are usually not of primary cardiac origin and tend to evolve gradually as progression from respiratory failure or shock states. Consequently, indicators of deterioration such as respiratory failure, bradycardia, and hypotension, often precede cardiac arrest due to the prevailing hypoxic component. The extended decline offers a timeframe for accurate and timely pediatric assessment that is not usually demonstrated in adult or neonatal cases. With appropriate assessment and treatment, complete progression to a cardiac arrest state can be avoided

Distinct consideration is merited for hypothermic patients without a palpable pulse. The progressive impact of hypothermia is characterized by substantial reduction in respiratory and heart rates. Consequently, the assessment duration for breathing and pulse should be extended to 60 seconds, accounting for the considerably diminished rates.

- Transportation of children in cardiac arrest should not minimize or lessen quality of CPR and ventilation. Consult with CliniCall if unsure of transport decisions in prolonged arrest states with no response to treatments. High quality CPR, appropriate ventilation, timely vascular access, and a moderate scene time (10 to 35 minutes) are proven elements that improve survival from cardiac arrest with good outcomes (Tijssen, 2015).

In summary, the infrequency of pediatric cardiac arrests portrays the significance of tailored management strategies emphasizing early, accurate assessment, high-quality CPR, and suitable interventions. These interventions stand to be pivotal in offsetting the complex physiological nuances that differentiate pediatric cases.

Essentials

American Heart Association Top 10 Cardiac Arrest Take Home Messages

- High-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the foundation of resuscitation. New data reaffirm the key components of high-quality CPR: providing adequate chest compression rate and depth, minimizing interruptions in CPR, allowing full chest recoil between compressions, and avoiding excessive ventilation.

- A respiratory rate of 20 to 30 breaths per minute is new for infants and children who are (a) receiving CPR with an advanced airway in place or (b) receiving rescue breathing and have a pulse.

- For patients with non-shockable rhythms, the earlier epinephrine is administered after CPR initiation, the more likely the patient is to survive.

- Using a cuffed endotracheal tube decreases the need for endotracheal tube changes.

- The routine use of cricoid pressure does not reduce the risk of regurgitation during bag-mask ventilation and may impede intubation success.

- For out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, bag-mask ventilation results in the same resuscitation outcomes as advanced airway interventions such as endotracheal intubation.

- Resuscitation does not end with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Excellent post–cardiac arrest care is critically important to achieving the best patient outcomes. For children who do not regain consciousness after ROSC, this care includes targeted temperature management and continuous electroencephalography monitoring. The prevention and/or treatment of hypotension, hyperoxia or hypoxia, and hypercapnia or hypocapnia is important.

- After discharge from the hospital, cardiac arrest survivors can have physical, cognitive, and emotional challenges and may need ongoing therapies and interventions.

- Naloxone can reverse respiratory arrest due to opioid overdose, but there is no evidence that it benefits patients in cardiac arrest.

- Fluid resuscitation in sepsis is based on patient response and requires frequent reassessment. Balanced crystalloid, unbalanced crystalloid, and colloid fluids are all acceptable for sepsis resuscitation. Epinephrine or norepinephrine infusions are used for fluid-refractory septic shock.

Additional Treatment Information

→ Post Cardiac Arrest Debriefing Checklist

→ Resuscitation Decision Making

For means of arrest guidelines/algorithms pediatric patients are infants, children, and adolescents up to 18 years of age, excluding newborns (0-29 days).

- Infant guidelines apply to infants younger than approximately 1 year of age.

- Child guidelines apply to children approximately 1 year of age until puberty. For teaching purposes, puberty is defined as breast development in females and the presence of axillary hair in males.

- For those patients with signs of puberty and beyond, adult basic life support guidelines should be followed.

Referral Information

All pediatric cardiac arrest patients with ROSC require emergency conveyance to hospital. Pediatric patients with a prolonged pulseless condition should be discussed with CliniCall. Non-viable or futile cases should also be discussed with CliniCall.

General Information

- Bystander CPR, plus early defibrillation, can more than double the rate of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. As such, paramedics and EMRs should carry out a full resuscitation in settings where first responder or bystander CPR has been initiated, unless obvious signs of death are present.

- Although survival from asystole or pulseless electrical activity is rare, patients who receive immediate, high quality CPR occasionally survive.

- Asystole in cardiac arrest is usually an ominous prognostic sign indicating prolonged hypoperfusion and myocardial ischemia with deterioration to asystole from more treatable dysrhythmias. Asystole must be confirmed in two or more leads.

- Pulseless electrical activity (PEA) is evidence of organized electrical activity on the ECG without effective myocardial contraction. Patients with wide complex PEA rhythms usually have poor survival and there are often indications of severe malfunction of the myocardium or cardiac conduction system. There are numerous possible causes of PEA, some of which are amenable to out-of-hospital treatment. Paramedics (and EMRs where applicable) should follow a step-wise approach to identifying and treating reversible causes of PEA.

- Special consideration must be given to hypothermic patients without a pulse. As hypothermia progresses, the patient’s respiratory and heart rate slow significantly. For this reason, breathing and pulse checks must be sufficiently long (60 seconds) to register very slow rates.

- “Circum-rescue collapse” is a term that describes a death that occurs shortly before, during, or soon after rescue from exposure to a cold environment, usually cold water immersion; it often presents as an apparently stable, conscious patient who suffers ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest shortly thereafter

- A patient with a core body temperature < 30°C will most likely develop arrhythmias with progression to ventricular fibrillation

- Medications are more slowly metabolized in hypothermic patients; limit vasopressors to a maximum of 3 doses; refer to → I01: Hypothermia for additional information

- The most common causes of traumatic cardiac arrest include:

- Hypoxemia from airway obstruction and hypoventilation

- Obstructive shock resulting from cardiac tamponade or pneumothorax

- Hemorrhagic shock from any source of major hemorrhage

- Myocardial contusions cause dysrhythmias, perforation, and valve rupture

- Electrical shock produces a fall; ventricular fibrillation may also be present

Interventions

First Responder (FR) Interventions

- Ensure high performance CPR and appropriate ventilation; chest compressions and ventilations should be provided at a ratio of 15:2 with pauses to allow for ventilation

- → PR06: High Performance CPR

- → B01: Airway Management

- Most pediatric airways can be effectively managed with proper positioning and an OPA/NPA (as per license level) and BVM without any requirements for further airway interventions. The gold standard for airway management is a self-maintained airway. Two-person bag-valve mask, with a viral filter attached and a tight seal, is the preferred technique for airway management in pediatric resuscitation and is reasonable compared with advanced airway interventions (endotracheal intubation or supraglottic airway) in the management of pediatrics during a cardiac arrest in the out-of-hospital setting.

- → A07: Oxygen Administration

- Apply AED and follow prompts

- Communicate clinical scenario to follow-on personnel

- Obtain clinical history from caregivers or bystanders

Emergency Medical Responder (EMR) & All License Levels Interventions

- Investigate for precipitating cause

- Ensure scene time is no less than 10 minutes and no greater than 35 minutes

- CliniCall consultation required for guidance in peri-arrest treatment planning.

- Seek assistance from additional resources.

- For low mechanism blunt trauma: continue CPR according to medical guidelines

- For penetrating trauma or high-mechanism blunt trauma:

- Immediately prepare for rapid conveyance and CPR (→ N04: Traumatic Cardiac Arrest)

- Control life threatening bleeding while facilitating conveyance

- Direct pressure to sites of obvious ongoing blood loss

- Rapid application of tight tourniquet for catastrophic extremity injury with ongoing large volume blood loss

Primary Care Paramedic (PCP) Interventions

Warning: primary care paramedics equipped with lifepak 15 monitor/defibrillators (LP15) must use an LP1000 AED when managing a pediatric cardiac arrest in children under the age of 8. Use of the LP15 in children under the age of 8 can result in electrical arcing, severe patient burns, and a significant fire hazard.

- Consider vascular access for reversible causes

- → D03: Vascular Access (in patients ≥ 12 years of age)

Advanced Care Paramedic (ACP) Interventions

- Attach monitor and evaluate rhythm

- Establish vascular access

- Ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia

- Defibrillate 2 J/kg, repeat at 4 J/kg

- EPINEPHrine

- Amiodarone

- Lidocaine

- Pulseless electrical activity or asystole:

- EPINEPHrine

- Consider treatable causes

- Bradycardia:

- Bradycardia with poor cardiac output requires chest compressions if the heart rate is < 60 and signs of poor perfusion are present; signs of poor perfusion include cyanosis, mottling, decreased level of consciousness, and lethargy

- Consider normal saline bolus 20 mL/kg IV/IO

- Consider EPINEPHrine

- Consider pacing

- → PR19: Transcutaneous Pacing

- CliniCall consultation required prior to transcutaneous pacing.

- Hyperkalemia, Torsades de Pointes, or suspected acidosis:

- Hypoglycemia

- Narcotic overdose:

- Assess for pneumothorax

Critical Care Paramedic (CCP) Interventions

- Aggressive fluid replacement including blood products for suspected hemorrhagic shock

- Aggressive re-warming if hypothermia present and suspected to be primary cause of presentation

- Ultranosonography to assess pneumothorax, tamponade, and cardiac contractility

- Post-return of spontaneous circulation care:

- Advanced airway

- Crystalloid bolus 20 ml/kg IV/IO

- EPINEPHrine infusion

Algorithm

Evidence Based Practice

Supportive

Neutral

Against

Supportive

Neutral

Against

References

- Alberta Health Services. AHS Medical Control Protocols. 2020. [Link]

- American Heart Association. Highlights of the 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR and ECC. 2020. [Link]

- Heart & Stroke. 2019 Focused Updates to AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC: Frequently Asked Questions. 2019. [Link]

- Tijssen JA, et al. Time on the scene and interventions are associated with improved survival in pediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. 2015. [Link]

Practice Updates

- 2023-10-06: updated guideline to align with Pediatric Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest educational program.

- 2023-05-24: changed AED with attenuated pads use threshold to < 8 years; above 8 years, LP15 use is permitted.